Found—a clipping from the mid Victorian Jerrold’s Weekly News regarding the legendary Sir Richard Phillips—a sort of Robert Maxwell of his time—and the witty physician, Dr John Wolcot (aka Peter Pindar).

‘Having mentioned Sir Richard Phillips, I must observe that his shop in Bridge-street was the lounge of a good many literary men. Philips was a shrewd man, fresh-coloured and stout. He lived to the age of eighty. He ate no flesh food, on the ground of his affection for animals. He had a notion in the latter part of his life, that he had discovered a system that would supersede Newton’s theory of gravity. Wolcot said that Phillips, notwithstanding his refusal of animal diet, had no objection to feed upon the brains of authors, and that he loved wine, but kept no beef-steaks. He referred here to Pitt, who it is said ‘would drink wines, but who kept no concubines’, in allusion to the notorious indifference of the Minister towards the fair sex. Walcot said that fact alone proved the Minister a great rascal. One of Pitt’s advocates, observing that it was no matter, Pitt was married to his country: ‘Yes’, said Wolcot, ‘and a cursed bad match it was for his country ‘. Now Doctor, that is too bad, was the reply: ‘You yourself have been but a bad subject of the King’. ‘It may or may not be so,’ said Wolcot, ‘but I can tell you the King has been an excellent subject for me ‘. Phillips used to call upon the doctor after the latter became totally blind, in order to get verses from him for the old Monthly Magazine. When he got them, so niggardly was Phillips, that the doctor could never obtain a second copy of the magazine to send to a friend. ‘I am constantly giving him something ‘, said the doctor. ‘When I ask for a couple of copies of my lines, he said I shall have them “at the trade price”. I will give him no more; ‘he is a Shylock.’ Continue reading

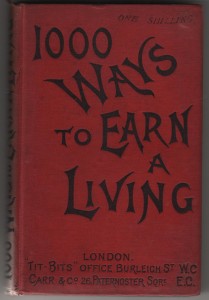

In the fascinating Thousand Ways to Earn a Living (1888) the section on ‘Literary Work’ covers journalism, authorship, and something called ‘compilation’. In the journalism chapter modern-day readers might be surprised at the high rates of pay awarded to humble London hacks ( up to £10 a week in 1888—more than a skilled surgeon or a junior barrister might earn ), but few could argue that in late Victorian Britain , as in 2017, in the newspaper world ‘ the majority of new ventures are promoted by newspaper men who have been underpaid or unfairly dealt with by their employers ‘.

In the fascinating Thousand Ways to Earn a Living (1888) the section on ‘Literary Work’ covers journalism, authorship, and something called ‘compilation’. In the journalism chapter modern-day readers might be surprised at the high rates of pay awarded to humble London hacks ( up to £10 a week in 1888—more than a skilled surgeon or a junior barrister might earn ), but few could argue that in late Victorian Britain , as in 2017, in the newspaper world ‘ the majority of new ventures are promoted by newspaper men who have been underpaid or unfairly dealt with by their employers ‘.

Few American publishers can boast that they have printed 300 hundred million books. Emanuel Haldeman-Julius (1889 – 1951), however, was one who could. An atheist and socialist who believed that the average American had a right to own a library of enlightening, useful and entertaining texts for a few cents a volume, Haldeman-Julius established the Little Blue Book series in the 1920s. Pocket-sized and ranging in subject matter from ancient culture and classic literature to self-help books and handbooks on making your own candy, the Little Blue Books sold in their millions each year, figured in the early education of such American writers as Saul Bellow and Studs Terkel, and anticipated in some respects the very popular ‘Dummies’ of today, though they were very much cheaper.

Few American publishers can boast that they have printed 300 hundred million books. Emanuel Haldeman-Julius (1889 – 1951), however, was one who could. An atheist and socialist who believed that the average American had a right to own a library of enlightening, useful and entertaining texts for a few cents a volume, Haldeman-Julius established the Little Blue Book series in the 1920s. Pocket-sized and ranging in subject matter from ancient culture and classic literature to self-help books and handbooks on making your own candy, the Little Blue Books sold in their millions each year, figured in the early education of such American writers as Saul Bellow and Studs Terkel, and anticipated in some respects the very popular ‘Dummies’ of today, though they were very much cheaper.

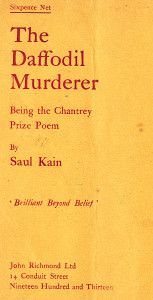

Found – a rather battered copy of Siegfried Sassoon’s early book The Daffodil Murderer (1913) published under the pseudonym ‘Saul Kain.’ In decent condition it has auction records like this from Bloomsbury Book Auctions in April 2009:

Found – a rather battered copy of Siegfried Sassoon’s early book The Daffodil Murderer (1913) published under the pseudonym ‘Saul Kain.’ In decent condition it has auction records like this from Bloomsbury Book Auctions in April 2009:

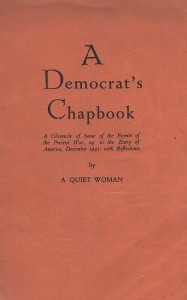

The identity of the ‘ quiet woman‘ who wrote A Democrat’s Chapbook (1942), a hundred page long commentary in free verse on the events of the Second World War up to the time when America joined the Allied forces, was only revealed when Anne Powell included two passages from it in her anthology of female war poetry, Shadows of War (1999 ). However, those who had read her volume of Georgian verse entitled Songs from the Sussex Downs ( 1915), a copy of which was found in the collection of Wilfred Owen, might have recognised the style as that of ‘Peggy Whitehouse’, whose Mary By the Sea also appeared under this name in 1946. All three books were the work of Mrs Frances Mundy –Castle (1875 – 1959).

The identity of the ‘ quiet woman‘ who wrote A Democrat’s Chapbook (1942), a hundred page long commentary in free verse on the events of the Second World War up to the time when America joined the Allied forces, was only revealed when Anne Powell included two passages from it in her anthology of female war poetry, Shadows of War (1999 ). However, those who had read her volume of Georgian verse entitled Songs from the Sussex Downs ( 1915), a copy of which was found in the collection of Wilfred Owen, might have recognised the style as that of ‘Peggy Whitehouse’, whose Mary By the Sea also appeared under this name in 1946. All three books were the work of Mrs Frances Mundy –Castle (1875 – 1959).