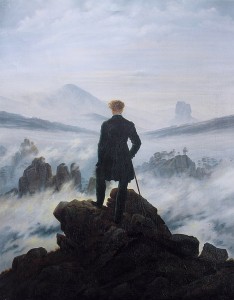

The journalist George Hutchinson (see previous Jots) was living in wartime Bradford when he visited High Withens, the supposed ‘ dwelling ‘ of Mr Heathcliffe of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Up on the lonely moors Hutchinson finds it hard to recognise that ‘England is at war’,

The journalist George Hutchinson (see previous Jots) was living in wartime Bradford when he visited High Withens, the supposed ‘ dwelling ‘ of Mr Heathcliffe of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Up on the lonely moors Hutchinson finds it hard to recognise that ‘England is at war’,

‘ Indeed, though the only indication in the whole locality is the scores of little evacuees and mothers, mostly from Bradford. The moor air and country rambles they have exchanged for city life should be of lasting benefit to these children and to many a mother, I am told, the rural beauty so near to Bradford has been quite a revelation—which in itself is salutary.’

Doubtless, in these days of local lockdowns, such salubrious open-air refuges from unhealthy urban landscapes, are appreciated for different reasons.

Hutchinson had already visited the Bronte Waterfall, not far from the Haworth Parsonage and this was not his first visit to Stanbury, the nearest village to High (or top) Withens, which he had never managed to reach before. On the way there he popped in to see the famous Jonas Bradley, former Head of Stanbury School and an international Bronte expert, at his home, Horton Croft in the village. Here he was invited to sign, not for the first time:

‘the third of the visitors’ books that Mr Bradley has kept since 1904. These books contain thousands of signatures, and his callers, they will tell you, have come from places as far apart as Glasgow and Godalming, Bulawayo and Brooklyn…’

This was probably the last time that Hutchinson saw Bradley, for he died early in 1943, aged 84, his obituary appearing that year in volume 10 of the Transactions of the Bronte Society, which he had helped to found many decades before. In this obituary Bradley’s reputation worldwide as a Bronte expert was confirmed. He had indeed been visited by ‘American University professors, statesmen, film directors and writers..’ Continue reading

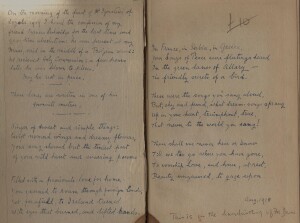

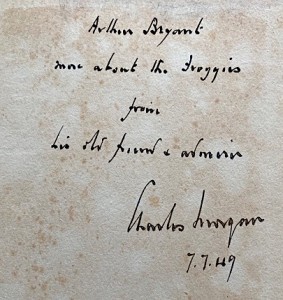

It’s always revealing to learn which books were the favourites of certain writers—and which books or writers were reviled. We know what Wyndham Lewis felt about the Bloomsbury set. It’s all in The Apes of God. It’s not a secret that Martin Amis worships Nabokov and Saul Bellow or that Kingsley Amis was a Janeite. The likes and dislikes of pre-modernist writers, however, tend to be less well known today, so it’s good to find someone expressing their secret admiration for a certain writer or a certain passage of prose or poetry.

It’s always revealing to learn which books were the favourites of certain writers—and which books or writers were reviled. We know what Wyndham Lewis felt about the Bloomsbury set. It’s all in The Apes of God. It’s not a secret that Martin Amis worships Nabokov and Saul Bellow or that Kingsley Amis was a Janeite. The likes and dislikes of pre-modernist writers, however, tend to be less well known today, so it’s good to find someone expressing their secret admiration for a certain writer or a certain passage of prose or poetry.

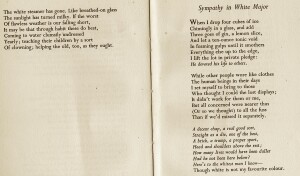

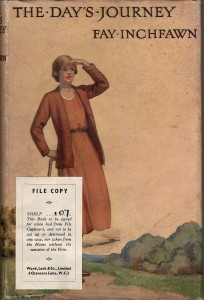

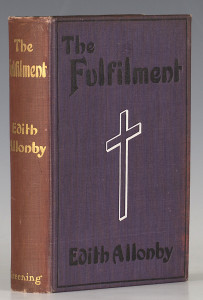

Discovered at Jot HQ is this first edition of one of the ‘Homely Woman’ pocket volumes by the prolific female writer Fay Inchfawn ( aka Elizabeth Rebecca Ward, 1880 – 1978), whose work is forgotten now, but whose books, which included popular verse, religious works and children’s literature, were once, to quote the blurb from her publisher Ward, Lock & Co in 1947, ‘to be found in countless homes, for more than half a million have been sold’.

Discovered at Jot HQ is this first edition of one of the ‘Homely Woman’ pocket volumes by the prolific female writer Fay Inchfawn ( aka Elizabeth Rebecca Ward, 1880 – 1978), whose work is forgotten now, but whose books, which included popular verse, religious works and children’s literature, were once, to quote the blurb from her publisher Ward, Lock & Co in 1947, ‘to be found in countless homes, for more than half a million have been sold’.

In the April 24th 1942 issue of John O’London’s Weekly can be found a perceptive view by the essayist Robert Lynd on the subject of risible poetry written by good poets. He takes his cue from an incident a century before when Thomas Wakley, the founder of the Lancet, stood up in the Commons to mock some puerile lines from ‘Louisa’ by the Poet Laureate, William Wordsworth.

In the April 24th 1942 issue of John O’London’s Weekly can be found a perceptive view by the essayist Robert Lynd on the subject of risible poetry written by good poets. He takes his cue from an incident a century before when Thomas Wakley, the founder of the Lancet, stood up in the Commons to mock some puerile lines from ‘Louisa’ by the Poet Laureate, William Wordsworth. found on her lap following her suicide, aged just thirty, in December 1905. When discovered she was sitting in a comfortable chair dressed in a silk evening gown with fresh flowers in her hair. By her side was an empty bottle of phenol (carbolic acid), the poison of choice (bleach was another) for many suicides in the UK at that time, due to its availability and quick, but painful, action.

found on her lap following her suicide, aged just thirty, in December 1905. When discovered she was sitting in a comfortable chair dressed in a silk evening gown with fresh flowers in her hair. By her side was an empty bottle of phenol (carbolic acid), the poison of choice (bleach was another) for many suicides in the UK at that time, due to its availability and quick, but painful, action.

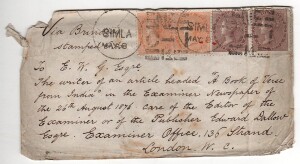

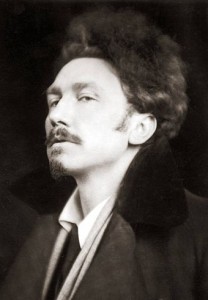

It’s often enlightening to read very early reviews of major writers, especially modernist writers. In 2019 we have the benefit of knowing how certain ‘ big names ‘ developed and influenced others, while the innocent reviewer of an early work has only the words on a page. A gifted reviewer may sense that a writer under review is destined for greatness, but most reviewers are hacks and care little. In the case of Ezra Pound, the anonymous review of his third collection, Personaethat appeared in The Literary Worldof August 15th1909, suggests that the reviewer was already an admirer of his first two collections, A Lume Spento(1908), which had been privately printed in Venice in a tiny edition of just 150 copies, but which Pound had persuaded the London bookseller Elkin Matthews to display in his window—and the follow up, A Quinzaine for this Yule—also in a tiny edition. A London Evening Standardreviewer described the former as ‘wild and haunting stuff, absolutely poetic, original, imaginative, passionate and spiritual’. It seems that the Literary World reviewer was of a similar mind:

It’s often enlightening to read very early reviews of major writers, especially modernist writers. In 2019 we have the benefit of knowing how certain ‘ big names ‘ developed and influenced others, while the innocent reviewer of an early work has only the words on a page. A gifted reviewer may sense that a writer under review is destined for greatness, but most reviewers are hacks and care little. In the case of Ezra Pound, the anonymous review of his third collection, Personaethat appeared in The Literary Worldof August 15th1909, suggests that the reviewer was already an admirer of his first two collections, A Lume Spento(1908), which had been privately printed in Venice in a tiny edition of just 150 copies, but which Pound had persuaded the London bookseller Elkin Matthews to display in his window—and the follow up, A Quinzaine for this Yule—also in a tiny edition. A London Evening Standardreviewer described the former as ‘wild and haunting stuff, absolutely poetic, original, imaginative, passionate and spiritual’. It seems that the Literary World reviewer was of a similar mind: