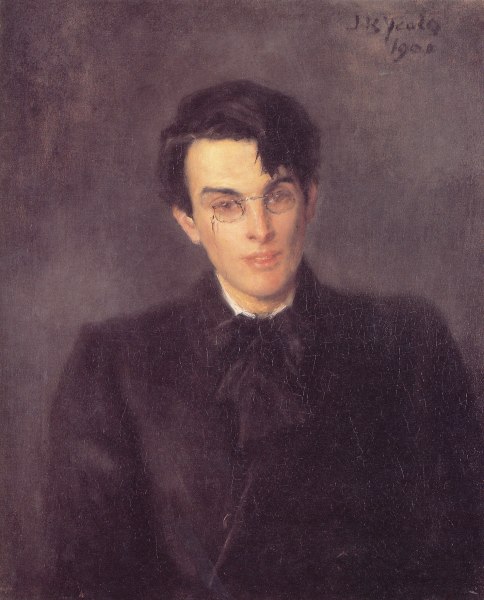

In ‘ Letters to my Great-Grandson ‘ ( in The Book of Fleet Street, ed. T. Michael Pope,1931) the journalist and art historian Anthony Bertram (1897 – 1978), pretends to be writing to his grandson in 1985 when he recollects seeing and hearing W. B. Yeats in 1921.

‘I remember going to tea with him when he lived in the Broad ( the old name for Shorthand Street at Oxford, before the University was absorbed by Pitman’s). The house was pulled down as long ago as 1929. I followed a servant up a steep flight of stairs and was introduced into a dim book-lined study in the attic. Yeats, with flowing tie and white hair straying forward, was standing before a high reading desk with tall candles burning on either side, and he was reading the Kelmscott ‘ Chaucer ‘. He signed to me without speaking, indicated the illustration before him and then proceeded slowly and reverently to0 turn the pages…’

‘I remember he came to lunch with me once in college. Oh, I was aware that Yeats was a celebrity all right. You see, he was of the older generation. So, I had the best college silver and ruined myself on wines and borrowed a coffee machine like an alchemist’s retort, a wonderful contraption of glass globes and spirit- lamps .My other guests were Father Martindale, a Jesuit of some notability, and Wilfred Childe, a delicate taper-like poet who afterwards became frightened by the vice and riotous of life and retired to Leeds. Yeats talked about fairies and just when he was quoting with wonderful sonority, the coffee contraption burst. Yeats did not even pause in his quotation, and I sat watching the black flood spread, not daring to interrupt. I do not know whether he failed to notice the calamity or mere ignored it. In either case he was superb.

I was very young then and I find that I made notes of some things that Yeats said on that occasion. Here they ae fo0r you, just as they were written down in 1921:’

‘Life is a striving after the antithesis. The passionate Landor wass the Phidias of poetry; the gregarious Shelley worshipped solitude; the active, quick Morris created men vague and detached.’

‘Christ was the antithesis of classicism.’

‘The man who gives up seeking for his antithesis becomes a don, a journalist or a country parson—something not quite human.’

‘The antithesis of a man is that virtue which is mo0st remote from him, yet not unattainable.’

‘The canker of modern art is the failure to recognise evil.’

‘Without horror there is a weak perception of beauty. Horror is a foil to beauty.’

‘Morris would not produce drama because the actors would not chant.’

‘Lionel Johnson remarked to me that not to believe in eternal punishment is to be grossly vulgar.’

‘Wisdom’s life is bitter. I have striven all my life to drug my intellect with philosophy. If I only read and thought about literature I should have nothing to write about.’

‘The key to philosophy is the law of history.’

‘ I am convinced that there are minds without bodies. I feel their presence and sometimes they are greater than me and dominate me.’

‘Milton is not enjoyed because of bad poets and worse theologians.’

So you see the sort of conversation it was and why the bursting of a coffee-contraption could not be allowed to interrupt…’

Continue reading

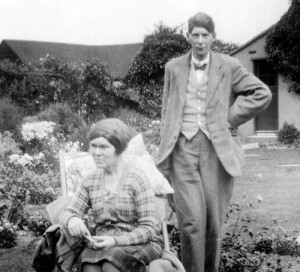

It is in The Last of Spring, one of Rupert Croft-Cooke’s many autobiographical volumes that one finds an account of the author’s experience of renting one of the Cornish bungalows built for writers by the eccentric spiritual medium and author, Mrs A.C. Dawson Scott, in the early 1930s.

It is in The Last of Spring, one of Rupert Croft-Cooke’s many autobiographical volumes that one finds an account of the author’s experience of renting one of the Cornish bungalows built for writers by the eccentric spiritual medium and author, Mrs A.C. Dawson Scott, in the early 1930s.