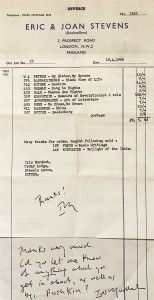

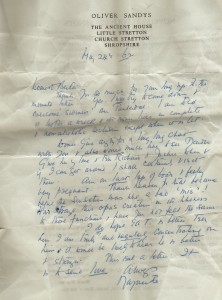

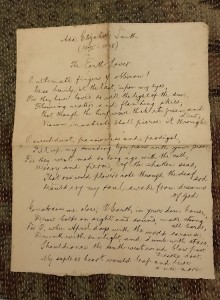

From the archive of the booksellers and publishers Eric and Joan Stevens is this carbon copy of a squib typed out by the poet John Heath-Stubbs and signed by him on 30 May 1963.I say ‘ typed out ‘, but as he was virtually blind by this time, and there are no typos, it is unlikely that he actually did so. In his later years the cult figure Eddie Linden, hero of the book Who is Eddie Linden?,read to Heath-Stubbs, so he may also have been a sort of amanuensis in the sixties.

The poem, which is entitled ‘Poetry Reading ‘and appears unpublished, pokes fun at various eminent and not so eminent literary figures of the period. The occasion was a meeting to commemorate a ‘notable Georgian poet ‘ and was arranged by ‘ The Organisation for Ossification Of Literatwitters ‘, which may be a swipe by Heath-Stubbs at the Royal Society of Literature, which had elected him a fellow in 1954.Identifying the poet being celebrated is not easy. Most of those who contributed to the famous Georgian anthologies were born in the 1870s and 1880s and weren’t around in 1963.The last of the genuine Georgians, Ralph Hodgson, died in 1962, so the poetry event may have occurred in that year or soon before. If he is ruled out the only other possible contender would be Edmund Blunden, although the ‘Merton field mouse’ (as Geoffrey Grigson called him ) isn’t generally regarded as a Georgian poet. However, Blunden did receive the Royal Society of Literature’s Benson medal.

The other literary folk ridiculed —the Chairman, ‘Estaban Heartsleeve ‘, ‘ Sandy Sladge of the Sunday Sludge ‘,‘ Sir Solon Sepulture ‘, ‘Mr Bang with his prizefighter’s roar ‘ and ‘Mr Bing’ —- are even more difficult to place, although the last two men, respectively ‘ tall and blond ‘ and ‘ short and pink’, should be a little easier to identify. The satirist reveals the name his friends knew him by (‘Stubbs’) at the close of the poem, as well as his avowed liking for alcohol and pub-going. He had been, after all, a prominent member of the Soho crowd in the ‘forties.

Today the RSL, perhaps aware of its past reputation for ossification, seems to have gone too far in the other direction. Seemingly anyone who has published at least two books, is well known as a reviewer for the nationals, and is a regular on TV, radio and at literary festivals, is offered a fellowship. Sadly, quite a few lack the literary skills of past Fellows. The Society also unashamedly reflects the current popularity of literary biographies and crime fiction to such an extent that the list of Fellows contains more writers in these genres than novelists, dramatists and poets. Many believe that by a too ready recognition of these doubtful genres as ‘literature ‘it has betrayed its original aims.

[R.M.Healey]

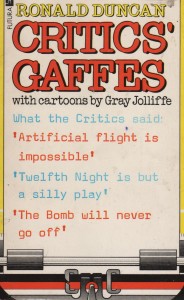

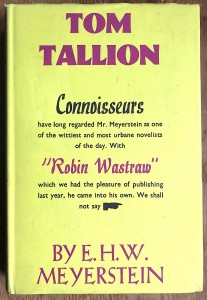

hilarious and sometimes shocking anthology, Critics’ Gaffes (1983), come from critics who supposedly know what they’re talking about. Others are the judgements of those who haven’t a clue. Perhaps Geoffrey Grigson nailed it when he described the romantic novelist and radio presenter Melvyn Bragg as ‘a media mediocrity who couldn’t tell good literature from old gym shoes.’ Mind you, like the stopped clock which tells the right time twice a day, a few of the following verdicts have the ring of truth.

hilarious and sometimes shocking anthology, Critics’ Gaffes (1983), come from critics who supposedly know what they’re talking about. Others are the judgements of those who haven’t a clue. Perhaps Geoffrey Grigson nailed it when he described the romantic novelist and radio presenter Melvyn Bragg as ‘a media mediocrity who couldn’t tell good literature from old gym shoes.’ Mind you, like the stopped clock which tells the right time twice a day, a few of the following verdicts have the ring of truth.

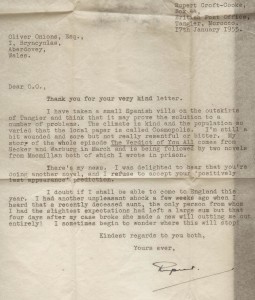

between consenting adults were made legal, many men from all backgrounds, including actors, writers and at least one famous mathematician, were prosecuted and sometimes jailed. The persecution of Dr Alan Turing, the genius who helped the UK win the Second World War, is a shameful blot on the English penal system, but another victim of the law whose conviction has aspects in common with that of Turing is the less well-known writer Rupert Croft-Cooke (1903 – 75).

between consenting adults were made legal, many men from all backgrounds, including actors, writers and at least one famous mathematician, were prosecuted and sometimes jailed. The persecution of Dr Alan Turing, the genius who helped the UK win the Second World War, is a shameful blot on the English penal system, but another victim of the law whose conviction has aspects in common with that of Turing is the less well-known writer Rupert Croft-Cooke (1903 – 75).

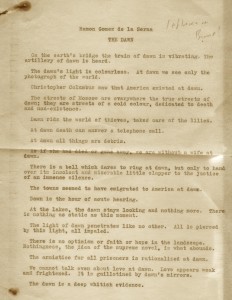

poem entitled ‘The Dawn’ by the famous Spanish experimental writer

poem entitled ‘The Dawn’ by the famous Spanish experimental writer

Connecticut 1928) – a special American edition. The great historian ‘s paean to the joys of walking (” I have two doctors, my left leg and my right..’) was published first as an essay in 1913 in Clio, a muse, and other essays literary and pedestrian and the American introduction by J. Brooks Atkinson notes that the walking world has changed much since then: “..the motor car has completely separated the walkers from the riders. It lays a new responsibility upon the walkers to conduct themselves nobly in God’s light.. they cannot be road walkers now, like Stevenson, since roads have become arteries -hardened arteries- of traffic. They are pushed willy-nilly into the hills, meadows and woods beyond the clatter and the evil fumes of the highway..” (he then launches an attack on the new walking clubs- ‘their walking is a bastard form of motoring.’) Trevelyan’s essay recalls a world now largely lost, although our great modern walkers (Iain Sinclair, Robert Macfarlane, Will Self) still find great places to ramble. GMT writes:

Connecticut 1928) – a special American edition. The great historian ‘s paean to the joys of walking (” I have two doctors, my left leg and my right..’) was published first as an essay in 1913 in Clio, a muse, and other essays literary and pedestrian and the American introduction by J. Brooks Atkinson notes that the walking world has changed much since then: “..the motor car has completely separated the walkers from the riders. It lays a new responsibility upon the walkers to conduct themselves nobly in God’s light.. they cannot be road walkers now, like Stevenson, since roads have become arteries -hardened arteries- of traffic. They are pushed willy-nilly into the hills, meadows and woods beyond the clatter and the evil fumes of the highway..” (he then launches an attack on the new walking clubs- ‘their walking is a bastard form of motoring.’) Trevelyan’s essay recalls a world now largely lost, although our great modern walkers (Iain Sinclair, Robert Macfarlane, Will Self) still find great places to ramble. GMT writes: